In the context of anti-war activities, the word «denunciation» is appearing in the news with increasing frequency. At first, a website to collect information about «saboteurs» was created by the Just Russia Party, then bots for denunciations sprang up in many regions, and then neighbors started informing on those who were hanging anti-war symbols in their windows.

On March 22nd, Nina Zolotukhina was arrested at a Moscow nightclub. Someone called the police about an anti-war statement she had made during a conversation. After that, Zolotukhina was jailed for 48 hours for using foul language while being arrested (Administrative Code Article 20.1).

These sorts of stories started appearing after the authorities began calling for denunciations. On March 21st, the «Just Russia—For Truth» party created a website where they would collect questions from Russians about shortcomings or omissions by the authorities, including those that may have been planned to intentionally do harm to the state. These questions were then supposed to be sent to the head of the Investigative Committee, Alexander Bastrykin as requests from Duma deputies.

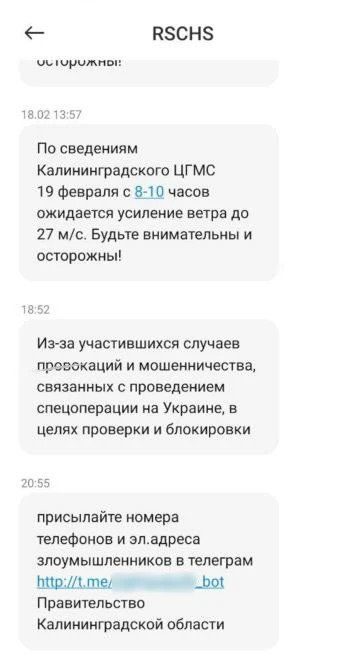

On that same day, a Kaliningrad resident started receiving text messages calling for him to denounce people who spread fake information about Russian military activities in Ukraine. The announcement was sent through the State Emergency Service’s alert system and was signed by the regional government.

«This was connected to the fact that we were already documenting a large amount, to put it mildly, of incorrect information circulating on social media, in various chats, etc.», said the regional administration’s press office.

The link in the text message leads to a Telegram bot with the letter «Z» in the colors of the St. George’s ribbon [black and orange] as its avatar. In the description, it says that it is «fighting provocateurs and scammers.»

A screenshot of the text message sent to the Kaliningrad resident as published in Novaya Gazeta.

Mediazona also discovered similar bots in six additional regions: Moscow, Altai, Belgorod, Penza, Saratov and Samara.

There is also a similar bot in Adygea. The initiative’s creators appealed to «concerned residents» who «are on the war path against anti-Russian propaganda, against attempts to sow divisions and to impose…defeatist and openly collaborationist views on our fellow countrymen.» Their call to report false information about the war was the pinned post on one of the Adygean Telegram channels. Below it was a list of people who these «concerned citizens» consider to be traitors. In addition to their names, their photos, screenshots of their social media pages, addresses and phone numbers were also published.

Direct denunciations soon followed. On March 19th, an unknown passerby denounced Maria Petrovskaya, an activist from Nizhegorodsk. She was on the street conducting a single-person protest with a poster reading, «Give birth yourself!» [OVD-Info—Send your own children to war!] with a drawing of the president holding a rocket like a baby. She was arrested.

В Нижнем Новгороде Мария Петровская вышла на площадь Свободы с антивоенным плакатом «Рожай сам». Одиночный пикет продлился около получаса, затем по доносу прохожего активистка была задержана. Марию доставили в ОП № 5, ей оказывают помощь правозащитники из проекта «Забрало». pic.twitter.com/niV3toqhx2

— Fem Antiwar Resistance (@femagainstwar) March 19, 2022

On March 22nd the police came to Moscow resident’s door for a check because he had hung strings of lights in the colors of the Ukrainian flag in his apartment window. A neighbor in the opposite building had reported it to the police.

Strings of lights in the colors of the Ukrainian flag on an apartment building/ Photo: Baza

The next day in the Altai Republic, neighbors reported the former head of the Turochakskii region Elena Unuchakova to the police. She had hung ribbons in the colors of the Ukrainian flag in her garden. The beat officer came to speak with her.

Ribbons in the colors of the Ukrainian flag in Elena Unuchakova’s garden, Altai Republic/ Photo: Baza

«The practice of denunciations is nothing new in Russia, ” says the head of OVD-Info’s legal department, Alexandra Baeva. «We’ve seen plenty of examples before now, ” she noted. «The only thing that differentiates the current situation is the rhetoric talking about how Russia is returning either to the 1920s and 30s, or as the Europeans think, to the years 1937-1939. Consequently, we are hearing the word ‘denunciation’ increasingly frequently. Usually it happens like this: a person comes to the police and reports that some person committed a crime and writes a complaint against them. The police then look into it, figure out the details of the case and then they might bring the person in to talk to them. And this is normal, if we’re talking about an actual crime, and not a politically motivated case.»

The number of reports from «concerned» citizens usually goes up during times when large protests are happening. That said, in Russia, it is unusual to see someone actually be prosecuted as a result of a denunciation, according to Baeva. She referred to one high-profile criminal case of nude photos in front of churches. Another well-known incident—the case against Yulia Tsvetkova an artist from Komsomolsk-na-Amure. A criminal case was opened after a report was filed by St. Petersburg «anti-gay warrior» Timur Bulatov.

«In terms of practice, denunciations don’t really change anything for us. But, we now see that the idea of denunciations is being talked about not just by random people on the internet, but also by high-ranking government officials. I think that people will take this as a call to action. We understand very well that repression comes not only at the hands of law enforcement, but also at the hands of those working in the state. And ordinary people also participate in this—some people genuinely, some under pressure, but repression comes at their hands too, ” said Baeva.

Karina Merkuryeva